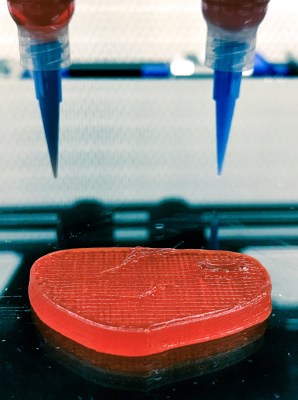

A video has been making the rounds on social media recently that shows a 3D printed "steak" developed by a company called NovaMeat. In the short clip, a machine can be seen extruding a paste made of ingredients such as peas and seaweed into a shape not entirely unlike that of a boot sole, which gets briefly fried in a pan. Slices of this futuristic foodstuff are then fed to passerby in an effort to prove it's actually edible. Nobody spits it out while the cameras are rolling, but the look on their faces could perhaps best be interpreted as resigned politeness. Yes, you can eat it. But you could eat a real boot sole too if you cooked it long enough.

To be fair, the goals of NovaMeat are certainly noble. Founder and CEO Giuseppe Scionti says that we need to develop new sustainable food sources to combat the environmental cost of our current livestock system, and he believes meat alternatives like his 3D printed steak could be the answer. Indeed, finding ways to reduce the consumption of meat would be a net positive for the environment, but it seems his team has a long way to go before the average meat-eater would be tempted by the objects extruded from his machine.

But the NovaMeat team aren't the first to attempt coaxing food out of a modified 3D printer, not by a long shot. They're simply the most recent addition to a surprisingly long list of individuals and entities, not least of which the United States military, that have looked into the concept. Ultimately, they've been after the same thing that convinced many hackers and makers to buy their own desktop 3D printer: the ability to produce something to the maker's exacting specifications. A machine that could produce food with the precise flavors and textures specified would in essence be the ultimate chef, but of course, it's far easier said than done.

Customized Cuisine

It should be said that there's no magic when it comes to printing edible objects. It's something that we've seen done many times at the hobbyist scale, from homebrew machines to the occasional official accessory for a commercial desktop 3D printer. At the absolute basic level, you simply replace the existing extruder and hotend with a syringe full of some sort of edible paste: peanut butter, dough, frosting, whatever.

It should be said that there's no magic when it comes to printing edible objects. It's something that we've seen done many times at the hobbyist scale, from homebrew machines to the occasional official accessory for a commercial desktop 3D printer. At the absolute basic level, you simply replace the existing extruder and hotend with a syringe full of some sort of edible paste: peanut butter, dough, frosting, whatever.

So far, it seems like the most headway has been made in ate because it has certain properties not entirely unlike the thermoplastic filament desktop 3D printers are designed for. If you warm it up enough it will extrude in a nice fine bead, and once it cools off, it will return to a solid state. Get the temperature and timing right, and the results can be quite impressive. During the 2018 Maker Faire we took a close look at the Cocoa Press, a perfect example of how these techniques can be put into practice today with existing technology.

Meals Ready to Extrude

Making custom shaped chocolates is a neat enough trick, and even has some commercial applications, but you're inherently limited by the single extruder design of the machine. Just like with plastic printers, the next step is to add multiple extruders or at least the ability to switch materials in the extruder. In theory, this would allow you to create complex foodstuffs that feature a mix of flavors, textures, and even nutritional values.

This is precisely what got the U.S. Army's Combat Feeding Directorate (CFD) interested in printing food back in 2014. The idea was that they could not only tailor battlefield rations to a specific soldier's appetite, but make sure it contained whatever vitamins and minerals they were currently deficient in. In principle, this means they could all but reduce food waste while at the same time making sure the enhanced nutritional requirements of a front-line combatant were met.

If this sounds a bit fanciful, that's because it is. To start with, being able to create food that fulfills the precise real-time nutritional needs of an individual requires some system to identify what those needs are quickly and easily; a technological capability that the CFD simply assumed would be available on the battlefield of the future. Further, the idea of a 3D printer complex enough to be capable of such feats while still being compact and robust enough for soldiers to carry into battle borders on science fiction. The mental image of a solder trying to diagnose why their printer wasn't extruding a particular flavor while hunkered down in a foxhole might be comical if the stakes weren't so high. Anything a solider takes with them must be reliable and robust to the highest degree possible, anything less could be a fatal liability.

That said, the other goals of the program: reducing waste by making custom portions and raising morale by allowing soldiers to create the type of food they actually want to eat, are areas where printed food does hold promise. As we've seen many times before, 3D printing works best when used to create a one-off customized instance of something, and the same holds true whether you're printing PLA or soy protein.

A Matter of Time

A machine that can produce a meal specifically tailored to the nutritional needs of the person who requested it is more akin to the replicators in Star Trek than anything we're likely to have in our kitchens in the foreseeable future. But a machine that can squirt out mashed-up peas into a vaguely steak-looking shape of whatever size you wish is clearly something we're capable of with contemporary technology. So why can't we order one from the latest Williams Sonoma catalog? For the same reason that 3D printing hasn't taken over traditional manufacturing: it's painfully slow.

A machine that can produce a meal specifically tailored to the nutritional needs of the person who requested it is more akin to the replicators in Star Trek than anything we're likely to have in our kitchens in the foreseeable future. But a machine that can squirt out mashed-up peas into a vaguely steak-looking shape of whatever size you wish is clearly something we're capable of with contemporary technology. So why can't we order one from the latest Williams Sonoma catalog? For the same reason that 3D printing hasn't taken over traditional manufacturing: it's painfully slow.

In the current incarnation of the NovaMeat printer, it can take twice as long to print a steak as it does to cook it. That might be acceptable for a proof of concept, but it will never work as a commercial product. It's even less practical for a restaurant, and completely unrealistic for large scale production. The process is limited by the physical constraints of moving an extruder around, and while there are certainly some optimizations that can be made (such as using a larger nozzle), these will only take you so far. The inherent "Speed Limit" of FDM printing has prevented it from displacing traditional manufacturing, and it will keep it from preparing our food as well. At least for the near future.

via http://bit.ly/2ICD60p

No comments:

Post a Comment